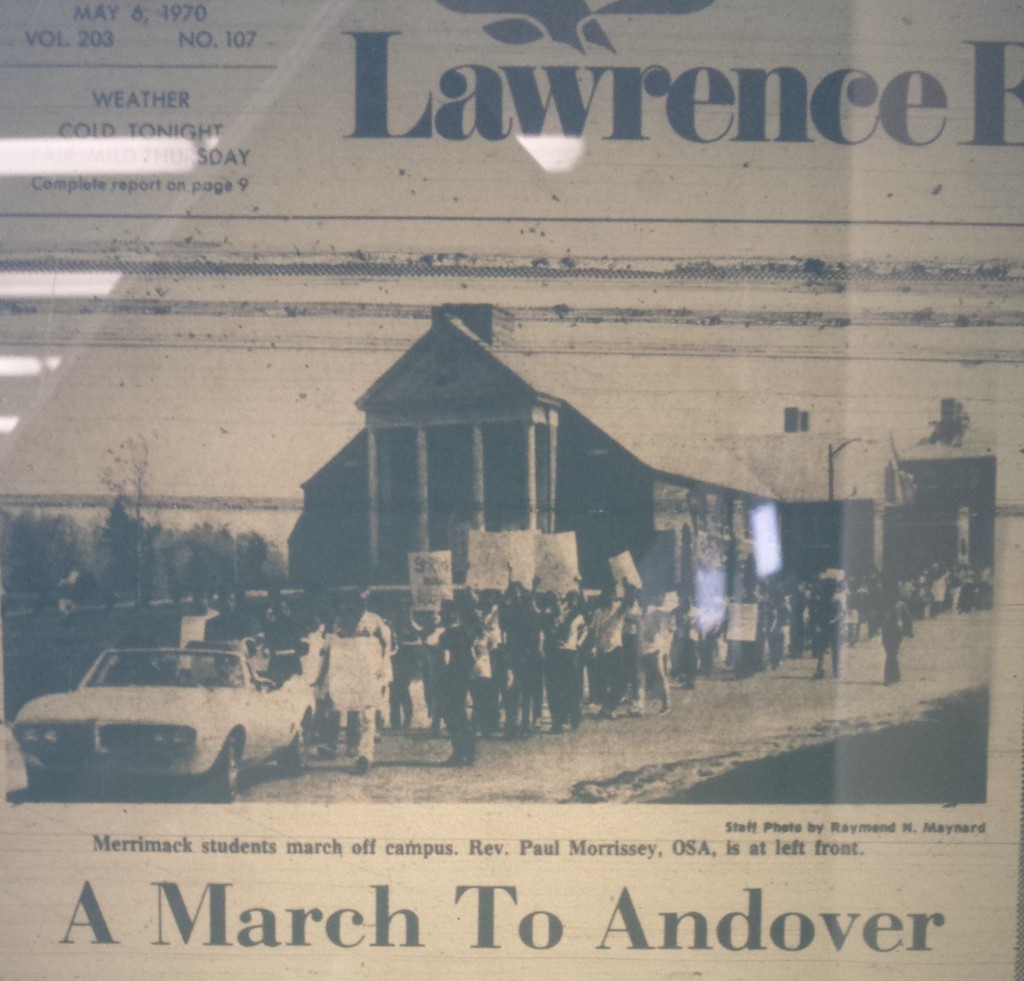

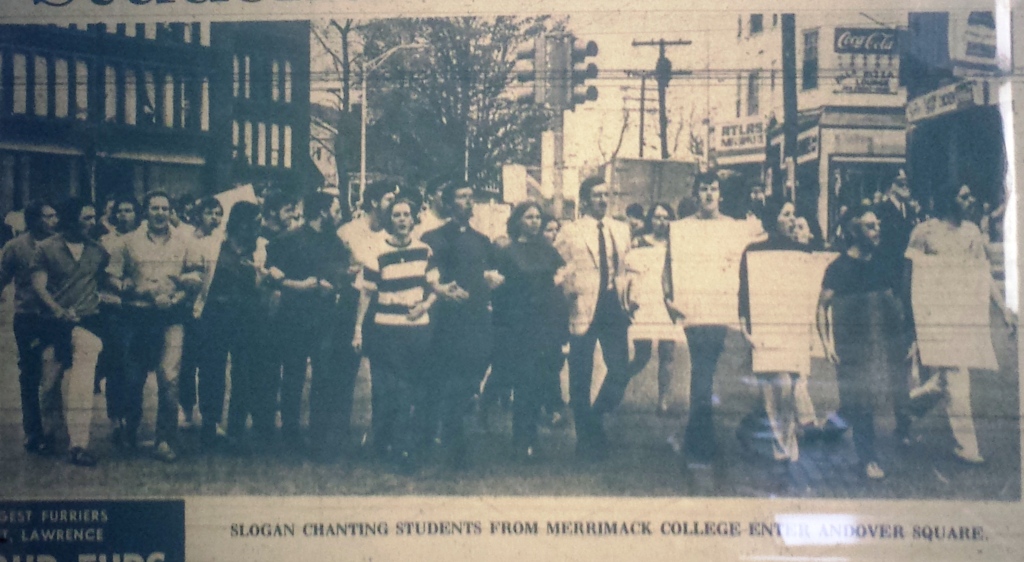

I didn’t go to my college graduation. The year was 1970, and student unrest over the Vietnam War had been boiling for some time. On April 29th, US and South Vietnamese forces entered Cambodia, and demonstrations immediately erupted on college campuses throughout the country.

The afternoon of May 4th was clear, with the jacket-weather crispness of early spring. I had driven up through Andover Center to the Merrimack College campus and was almost to the student parking lot. The car radio interrupted its broadcast; four students had just been killed on the campus of Kent State, shot by Ohio National Guard troops. I remember clearly my first emotion; “they’re killing us.” In the light of history, the categories of “they” and “us” were complex, but for myself, and thousands of other college students at the time, there was no confusion. The shootings were a sharp personal assault, and life just could not go on as before. So by the end of the day, the students of Merrimack College, along with those in over 450 colleges and universities around the country, were on strike.

Merrimack was a small college at the time. It was founded in 1947, just after World War II, by a Catholic order of priests (the Augustinians,) who projected a need for colleges in the suburbs of Boston to educate the returning soldiers from World War II and the subsequent baby boom. In 1970, with 2000 students and 500 in each class, it was smaller than many urban high schools. Classes were small, the professors were accessible, and there was only the large cafeteria and basement lounge in the student union for common areas. There was a real sense of community among the faculty and students.

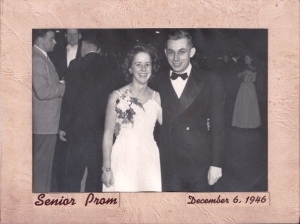

So when the strike was declared, it was a personal thing, a rift in the family. And it wasn’t just a rift between students and faculty. For two years, I had been part of a loosely organized on-going game of hearts in the basement lounge of the student union. Of the six or eight guys that floated in and out of this game, half of them were older ex-servicemen getting their college education on the GI bill. All of them had been involved in the ongoing war in one way or another. Their beliefs and priorities were very different from those my age who still faced the draft and service in Vietnam.

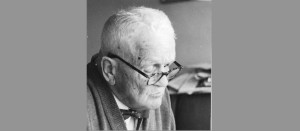

For me, the rift in the college community was even more personnel. My father began his teaching career at Merrimack College, when the college was a tiny affair operating out of a gym and some other temporary buildings. After several years, he left Merrimack to teach at the University of Maine in Bangor. In 1958, when I was 10, the college had grown large enough to have a separate Mathematics department, and my father returned as the first chairman. I had been in and around the school for most of my life. I knew the smell of every classroom, the rumble of every elevator. I knew nearly all the faculty: the faint Italian accent of the engineering professor Mr. Parotta, the laugh and mannerism of the half dozen members of the Math department. As a child, I could walk past waiting students into my father’s window office, and put my feet up on his desk if he wasn’t around.

The details of the strike have faded. It was much the same across the country; the students formed a committee, a list of demands was created, there were negotiations. Agreements were made about more student input into the college. But the strike was not about the school really. There was a much bigger drama being played out, and this small school was just one little act. Looking back, what I now appreciate was the grace with which the school, the administration and the faculty, handled the whole thing. There was no panic, there was no retribution that I remember. There were meetings. I remember that Dr. Parotta, a native of Italy where the political spectrum is much more vivid and above board than in America, asked a group of us exactly what was it that we wanted. Our lists made little sense; we wanted so much, and really nothing that they could offer.

I don’t remember if classes ever resumed. The semester fizzled to an end. A graduation was held, but I had no heart for it. In my sadness and rage at a deeply divided country, I was walking away from a longtime love, and there were no words or actions that could stop me.

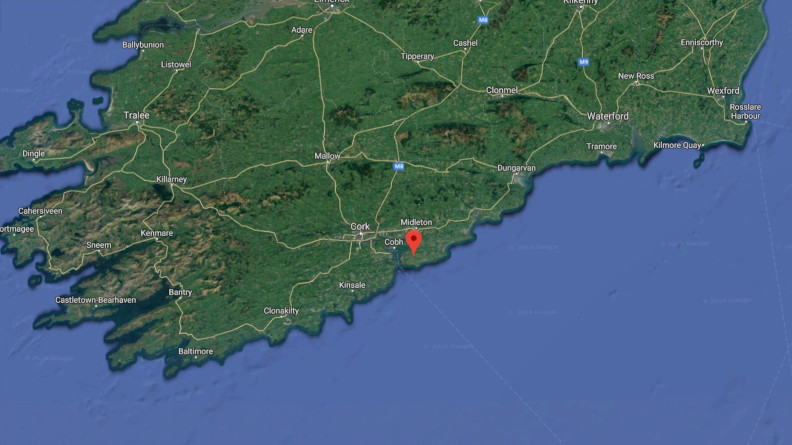

Ballinrostig

Ballinrostig